The following essay was read by Margo Taft Stever on Friday, May 9th, 2025, at the Harvard Club of New York City as part of a special event celebrating the new anthology What the Presidents’ Read: Childhood Stories and Family Favorites, edited by Elizabeth Goodenough and Marilyn S. Olson (Rowman & Littlefield, 2025). Ted Widmer, author of Lincoln on the Verge, wrote the introduction.

Searching for the Young William Howard Taft

William Howard Taft was born on September 15, 1857, the year of the Dred Scott decision [in which the Supreme Court justices decided that even though Scott had lived as a free person, he was not entitled to freedom]; the Indian Mutiny against British rule; and the laying of the Atlantic Cable for the telegraph.

His parents, Louise Torrey and Alphonso Taft, had lost their first child to whooping cough at fourteen months, a year before Will was born. His parents were overjoyed to welcome Will, who his mother would notice was large for his age at two months.

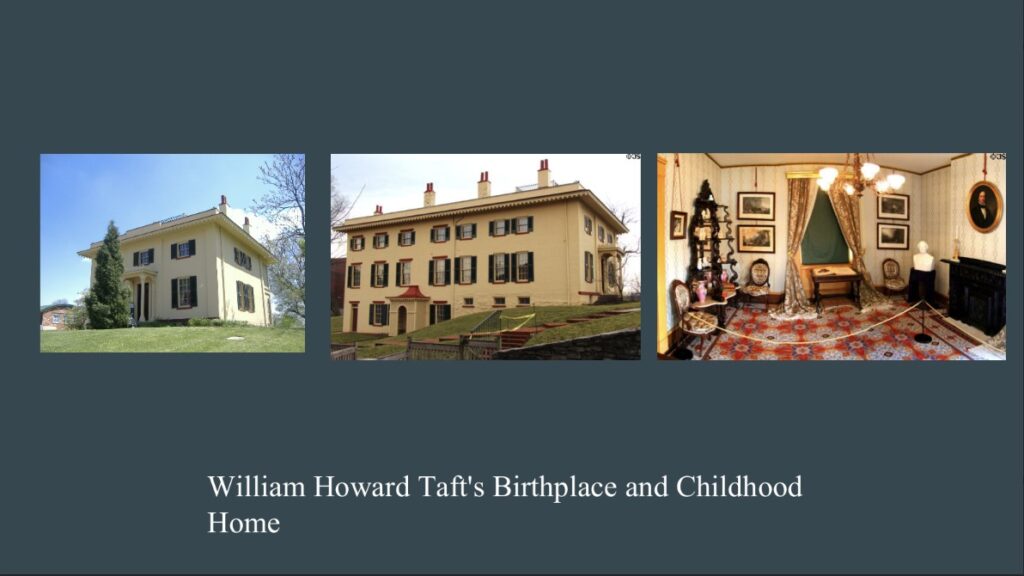

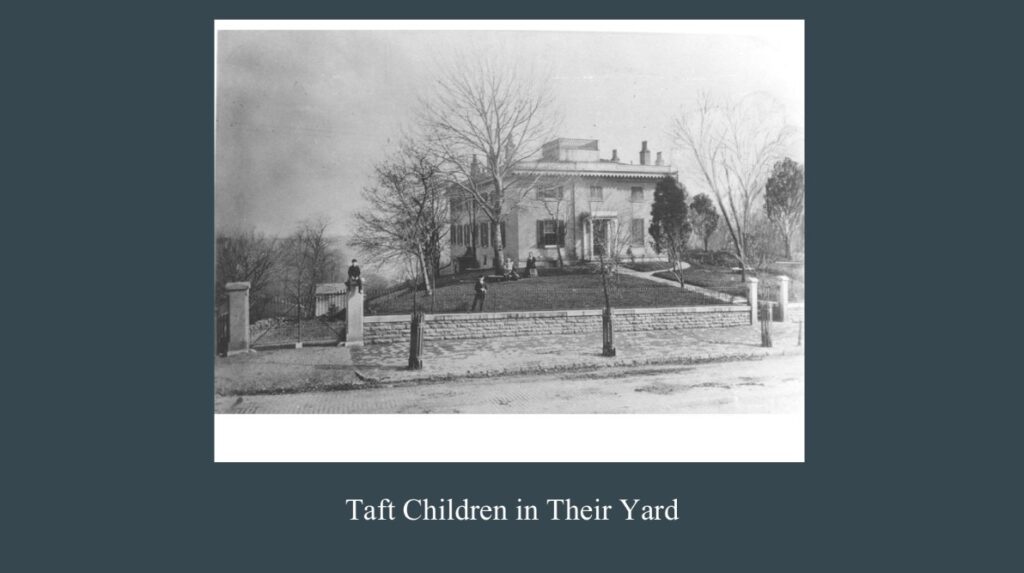

The square-shaped yellow brick Taft family house in Mt. Auburn sat back from the road in a respectable neighborhood located on one of the many hills outside of Cincinnati. Will and his family, including his grandparents, would gather around the fireplace in the parlor and read literature such as Aesop’s Fables and Shakespeare, images from which illustrated the Minton Tiles that they had installed around the fireplace.

Their commitment to the tenets of the Unitarian Church formed the basis of the Taft family’s firm belief in egalitarianism. Because of his parents’ and grandparents’ careful tutelage, Will would become a “conservative feminist” who believed that women were intellectually equal to men if they were provided with educational opportunities.

As a toddler, Alphonso described Will as active and happy, the one “to make the best of the ills of this life.” His parents said of him, “He means to be a scholar and studies well…He has a kind of zeal that is his own.” Will’s long list of activities included: baseball, bowling, dancing, wrestling, boxing, lifting weights, and calisthenics.

In the house, the older Taft children enjoyed whist, a card game popular in the 18th and 19th centuries, and chess. As youngsters, the Taft children played marbles and sandlot baseball. During summer, Will could be found climbing trees to pick apples and grapes. The older boys often explored the woods where they would engage in fishing, learning to swim, and hiking. They also participated in football and shinny, a kind of pond hockey played on ice.

Though Louise tried to discourage them, the boys fought. Because Will was so large and muscular, he was not allowed to attack his brother, Horace, but he acted as arbiter during his younger brothers’ frequent battles.

According to Doris Kearns Goodwin and other Taft biographers, during his childhood, Will Taft was motivated by an intense desire to please his parents who expected excellent academic performance. The Taft children enjoyed reading books by Scott, Thackeray, and Cooper, and for fun, the Oliver Optic books.

Despite his weight, Will was always known to be light on his feet; he had a reputation as a tough fighter and a good dancer. Because he had worked on wrestling, he knew how to defend himself. Although he was good-natured, when hard-pressed, he would battle with the gangs that inhabited Butchertown below Mount Adams.

Will graduated first in his class from grammar school. His parents built a wall around the property upon which the Taft children frequently perched, dangling their legs down the sides.

All the boys attended Woodward High School, an imposing and stern edifice that housed a school with strict standards and an excellent reputation.

During the war years, the boys went to Sunday school at Western Unitarian Conference School. Will was described as tractable and well-behaved. About Will’s character, one of his younger brothers opined, “It was very hard for anyone to be near him without loving him.”

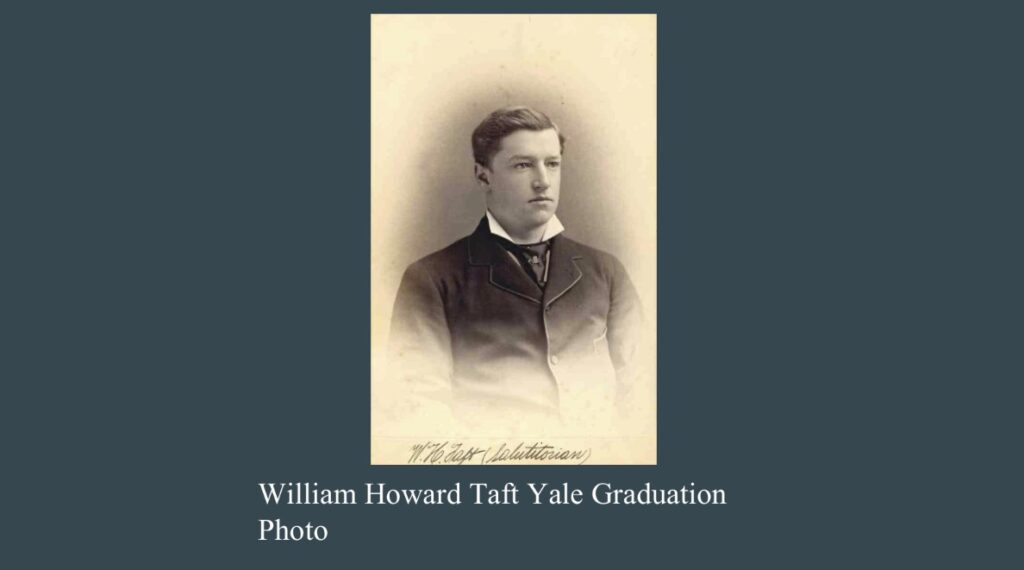

From Woodward High School and Yale College, Will graduated second in his class. Even so, Alphonso expressed worry about his work ethic and his tendency for laziness. His older half-brother, Peter, had set a high standard of not only graduating first in his class at Andover, but also at Yale where he was the best student ever. Horace remarked, “We felt that the sun shone brighter if we brought home good grades.”

When Will entered Yale, he was part of the first division of the freshman class of 1874. Alphonso wrote to Will’s grandfather, Samuel Torrey, “Willie is foremost, and I am inclined to think that he will always be so.” By his entrance to the freshman class, Will stood six feet high and weighed 225 pounds. He was called “Big Bill,” and his friendliness and interest in reaching out to all students made him one of the most popular in the entire class. His affable personality, imposing stature, and egalitarian and curious nature fostered by his upbringing would be a springboard to his political destiny.

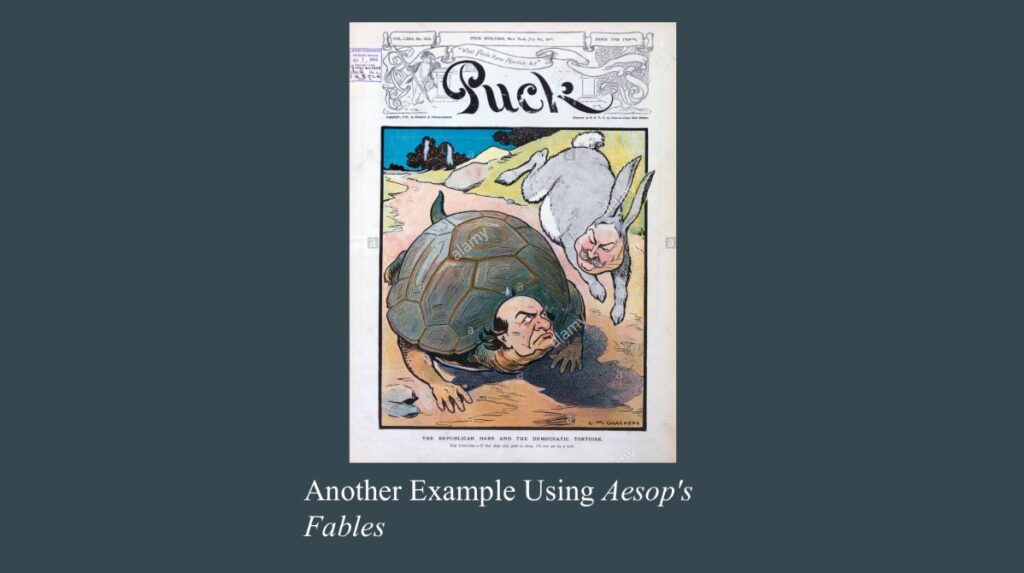

In this artful caricature of the political race of 1909, William Jennings Bryan and William Howard Taft are depicted as the tortoise and the hare. The Bryan and Taft cartoon with a fable exemplify the power of political caricature using children’s imagery as satire. This cartoon was published in Puck Magazine during July 1908. Taft served as U.S. president from 1909–1913, and after his painful split with Theodore Roosevelt who formed the Bull Moose Party, he lost the next election to Woodrow Wilson.